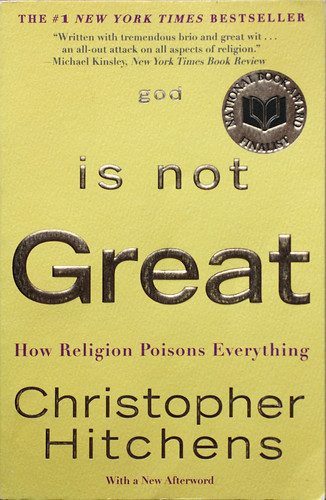

Author: Christopher Hitchens

Year: 2007

Genre: Religion, Philosophy

Publisher: Twelve

ISBN 978-0-446-69796-5

Book’s Wikipedia page

Author’s Wikipedia Page

Summary

Misusing capitalization in much the way it sometimes misuses facts, god is not Great is Christopher Hitchens’ tirade against the evil of religion; it is his most-recommended book in atheist circles. A former journalist, Hitchens is known to atheists as one of “The Four Horsemen" — along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett — the most famous advocates of non-religion of their time.

In this book, Hitchens begins with a 75-word sentence and rarely composes a shorter one. He writes as if holding back a flow of even more words, as if terrified of running out of time. And run out of time he did, in 2011, long before I knew his name.

The book is a polemic, an organized and systematic attack on the very idea of religion, and especially on the privileged place of “respect” it occupies in even the most educated nations today.

What I Liked Least About It

Most criticisms of god is not Great focused on the perceived insults to respected religious figures and beliefs, which is all well and good because that was its intended purpose. Hurt feelings among the dogmatically theistic was not a happy byproduct of Hitchens’ assault; it was the target.

I had three problems with it.

From the first sentence to the final few pages, the author constructs sentences and paragraphs as if building a verbal Tower of Babel, hanging words and phrases atop each other willy-nilly, chopped up with a multitude of commas, semicolons, em dashes, and parantheses. The impression is strong that the paranthetical phrase is his favorite literary device. Here are two examples that I flipped to randomly:

“Now that the courts have protected Americans (at least for the moment) from the inculcation of compulsory ‘creationist’ stupidity in the classroom, we can echo that other great Victorian Lord Macaulay and say that ‘every schoolchild knows’ that Paley had put his creaking, leaking cart in front of his wheezing and broken-down old horse.” “Long before modern inquiry and painstaking translation and excavation had helped enlighten us, it was well within the compass of a thinking person to see that the ‘revelation’ at Sinai and the rest of the Pentateuch was an ill-carpentered fiction, bolted into place well after the nonevents that it fails to describe convincingly or even plausibly.”It might seem a strange criticism from me, someone also known to bloviate loquaciously, but no one has ever held my prose out to be “elegant yet biting” — as reviewer Bruce DeSilva said of Hitchens.

Secondly, I found myself doubting some of the more obscure claims from history. Not being an erudite scholar myself, I searched online and indeed found similiar criticisms of god is not Great (in that link, scroll about halfway down before this book is mentioned). Christian David Hart rightly points out several factual errors by Hitchens — including mixing up two different Crusades, claiming two men who died of old age were instead burned at the stake, and others. These errors would be acceptable in off-the-cuff spoken remarks — or even a blog or shoddy newspaper article — but are surprising and disappointing in a published tome with eight pages of dozens of references at the end. For me, someone who highly values factual verification, each unverified or doubtful claim further eroded my confidence in the book.

Lastly, the tendency to base every point on excessive anecdotal elaboration was disappointing after having recently read Bertrand Russell’s logically-stated essays. Illustrative yarns are important even in nonfiction, for the purpose of elucidation, but should never be the foundation of definitive pronouncements. I expected better of such a respected and knowledgeable writer, even if it’s uncertain he intentionally employed terminological inexactitude.

What I Liked Most About It

From the book, there is no question why Hitchens is considered a go-to source for quotations when it comes to skepticism and atheism. His most famous line, now immortalized as Hitchens’ razor came from this book (though he’d used it before):

“What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”Here are a few others:

“Human decency is not derived from religion. It precedes it.”Further, I like that he does not attack one religion only, giving a pass to the mystical “Eastern” doctrines as do many skeptics in the West. He fully deals with Hinduism and Buddhism as well, and groups all faiths into one basket. Entry to this basket requires only two things: ridiculous assertions about the imaginary beings and demands that we must believe them on faith alone.

“One must state it plainly. Religion comes from the period of human prehistory where nobody — not even the mighty Democritus who concluded that all matter was made from atoms — had the smallest idea what was going on. It comes from the bawling and fearful infancy of our species, and is a babyish attempt to meet our inescapable demand for knowledge (as well as for comfort, reassurance and other infantile needs). Today the least educated of my children knows much more about the natural order than any of the founders of religion, and one would like to think — though the connection is not a fully demonstrable one — that this is why they seem so uninterested in sending fellow humans to hell.”

“Many religions now come before us with ingratiating smirks and outspread hands, like an unctuous merchant in a bazaar. They offer consolation and solidarity and uplift, competing as they do in a marketplace. But we have a right to remember how barbarically they behaved when they were strong and were making an offer that people could not refuse.”

Conclusion

From my trio of grumpy condemnations above, one might conclude I disliked this book overall. One would be wrong. My net takeaway is that it was worth reading, but that it could have been better. Certainly no religious person would read this book and be convinced — I say with my own experience as a Godist in mind.

But perhaps that wasn’t the point. Maybe Hitchens’ intention was simply to bolster the confidence of the minority of humans who look at the world rationally. Maybe it to was to ruffle a few feathers — which it certainly did. Certainly it served to work a few phrases into the common vernacular. "Religion poisons everything" is now used on occasion; I've seen it in online discussions on a somewhat frequent basis. Presumably those using the phrase know it came from this book. Even if they don’t know, success has been had.

Anticipating that someone might ask me how it compares to Dawkins’ The God Delusion, I answer thusly: these books are two different critters, for two different types of readers. Everything else being equal, I would recommend Dawkins’ book over this one.

comments powered by Disqus